This article is a continuation from part 1

It is often assumed that bad animation are the result of animation studios having to cut the number of frames to cut on paper expenses. This creates the assumption that “if the studio had money, they would not need to cut down the number of frames for animation”. The concept of limited animation has been introduced in the previous part, and in this second part, it will be explained further how the application of limited animation relates to that assumption.

Fewer Frames? No Problem!

Is it true that only animation with high frame rate and fluid movements can be considered as good animation? Back in the 60s, that was the standard that was held firm. But nowadays, that is no longer the case. In the previous part, it has been explained how limited animation differs from Disney’s full animation. Thanks to the efforts of Otsuka, Miyazaki, and Takahata, Japan’s animation industry experienced the auteur boom in the 70s to 80s, or also known as progressive anime, where both directors and animators compete and experiment to show their uniqueness, and then creating their own identity. Limited animation opens new possibilities and chances for these animators. It creates idiosyncratic (individually unique) animation styles which still affect the visual in anime nowadays.

According to Thomas Lamarre, limited animation triggers a crisis to classic full animation model. Because of the need to fulfill certain standards to create fluid movements, full animation may be suspectible to stick into certain clichés. Meanwhile, because movement in limited animation tends to be present as a potential, it provides a space that encourage some kind of individuation, where animators can express their individual unique styles. This also leads to the growing importance of character design, where distinctive character appearances were made by directly inscribing the personality of the characters into the surface appearance, making the characters able to move easier between different forms of media.

Furthermore, Lamarre argues that the consequence of applying limited animation also drives the development of creative expressions from the viewers, through fanart, doujinshi, garage kit (figurine or homemade character/robot model), to cosplay (acting as a character using their costume). However this will not be discussed further as it is not in the scope of this article. You can learn further about it by reading the chapter “Full Limited Animation” in Lamarre’s book “The Anime Machine: A Media Theory of Animation.” The most important point is, as quoted by Lamarre from animation critic Takuya Mori, that limited animation has its own art and experimentation like full animation, and can even break the distinction between commercial and experimental productions.

As an example of how animators can create their own unique style, we can take example from the late Yoshinori Kanada. Kanada is often called as the father of Japan’s modern animation. In stark contrast to Disney’s fluid animation, Kanada’s animation minimize the number of frames and push limited animation to the extremes. He also drew objects and effects with exaggerated forms/poses/perspectives, which makes the objects and effects in his animation look as though they are leaping from one frame to the other. Kanada got recognition with this unique individual style, which is exemplified in the opening sequence of Ginga Senpuu Brainger anime.

His unique style, which was then called as “Kanada School Style of Animation”, successfully inspired many other animators. Until this day, Kanada School Style of Animation is still used and developed by many animators, such as:

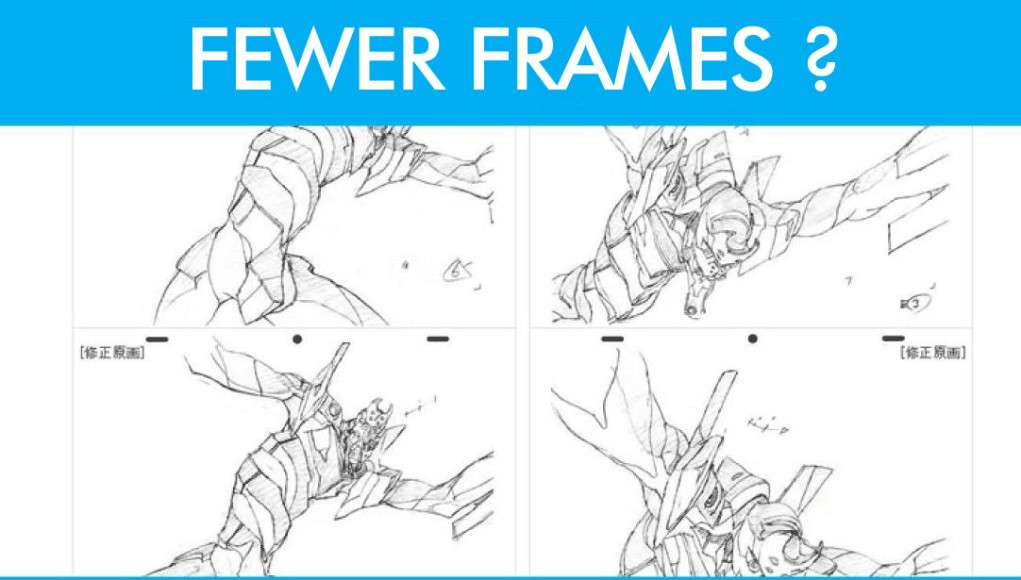

Star Driver episode 25 – Key animator : Hiroki Mutaguchi (freelance animator)

Gurren Lagann Parallel Works – Key animator : Akira Amemiya (animator/director from Studio Trigger)

FLCL Episode 5 – Key animator : Hiroyuki Imaishi (animator/director/co-founder Studio Trigger) ; Imaishi’s personal style often called as “Neo Kanada Style”

You can see how they utilize a small number of frames to make movements that looked choppy and exaggerated, but still dynamic and powerful. Kanada School Style of animation is a style that emphasizes on the intensities in each frame. Production committee may give these animators all the money and time that they can give, but these animators would still produce animation like that because that’s their personal choice of style.

Another example of utilizing limited number of frames effectively can be found in the works of animator Mitsuo Iso. Iso is often considered as an animator with one of the best techniques in Japanese hand-drawn animation, and other animators recognize him as a genius among geniuses. Iso felt unsatisfied with Japanese animation in the 80s, which look unnatural because of overly stiff inbetweens. Because of that, Iso wanted total control of his work and chose not to use any inbetween at all. This is how Iso creates his own style which was later called “Full Limited” Style, because every animation he worked on is created only in 2s and 3s with no inbetween. The result is very realistic and detailed animation that creates real momentum and impact, and also gives strong impression to the viewer. Unfortunately, unlike Kanada School Style of Animation, Iso’s Full Limited Style is really difficult to use or imitate by others, making this technique can only be implemented by few other animators.

Neon Genesis Evangelion : End of Evangelion – Key animator : Mitsuo Iso (freelance animator/director)

Ghost in The Shell (1995) – Key animator : Mitsuo Iso (freelance animator/director)

Sword Art Online II – Key animator : Tetsuya Takeuchi (freelance animator)

The assumption that animation studios have to cut the number of frames because of limited budget, thus lowering their animation quality, probably emerged because that problem happened frequently in anime production during the 60s. But then, along with the utilization of limited animation and diversification of individual styles, many animators nowadays can easily solve the problem of limited number of frames. In the end, the solution of this problem is not money, but through the skills and efforts from the people in involved in the production of anime.

To be continued in part 3

The Indonesian Anime Times | Original text by Yoza Widi and Halimun Muhammad | Translation by Dany Muhammad

Always interesting to read or re-read about that. I believe though that Disney isn’t always animating on 1s, and mostly on 2s (though there are parts on 1s).

I think that full animation also covers the level of detail of the production, secondary action, background animation, things like that and not only the main characters moving on a still background.

Though those are only terminology matters and I’m not ever sure about that.

I heard ghibli is the one that does that, and disney mostly animated on ones. But I may have to do some re-check about that.

Regarding the latter, it’s true, while animating only a certain “parts” of an object is also one of the foundations of limited animation, yet nowadays, I believe things like secondary animation and bg animation aren’t entirely absent from limited animation. We often see them animated on 2s and 3s now, and thus, it’s rather difficult to use them as parameters for differentiating between limited / full animation.

Well, the other reason I didn’t mention that was because of the purpose of his article itself. Since I wrote this with indonesian audience in mind. And most of them often think that the amount of frame is preeminent in determining an animation quality, hence the title. So, I wanted the article to be focused more on that

Yeah I understood your goal, no worries.

It’s true for secondary action in some anime (Space Dandy for one), thus I find it hard to differentiate “limited” from “full” nowadays with the evolution of the mentalities (of the animators themselves), I don’t like these terms that sounds kinda depreciating, for limited animation. They are too vague and do not comprehend things like level of detail of an animation drawing, which is an interesting factor too.

“The result is very realistic and detailed animation that creates real momentum and impact, and also gives strong impression to the viewer.”

For me, that’s absolutely false. The camera is too close. They should zoom out and keep it that way for a long time. I never liked this type of animation; it’s horrible.

But now I understand that money wasn’t the issue, but the animators. So, Japan isn’t an option for making anime with a wider shot.