Lately, I have been observing the term “gatekeeping” often being used by anime fans on social media. As student of media studies, this usage of the term by anime fans confused me because I’m more familiar with the concept of gatekeeping as formally identified by Kurt Lewin, which refers to the process where information is filtered by media—more on this later. Thus, I looked more into this different meaning through conversing with a friend who is more familiar with the use of the word among anime fans. From the conversation, I came to realize that their understanding of “gatekeeping” is more akin to the practice of art appreciation.

But seeing a form of discourse usually found in the appreciation of high art being practiced in regard to anime and manga only invited more questions. When it comes to high art, only a few select people can appreciate a work. However, following MacWilliams’ typology (2008), anime and manga are closer to mass art, a type of art that aims to gather as many audience as possible. So, why do some people on the Internet trying to “gatekeep” media that are targeted at the masses? And how is Lewin’s idea of gatekeeping relevant to this issue? These are the matters that I’d like to discuss in this article.

Gatekeeping: Protecting Culture or Exclusivity?

According to Jensen & Verboord (2015) and An & Cerasi (2017), gatekeepers in high art (think of the kinds of works typically shown at museum and art galleries or exhibitions) are select few people like curators or major art collectors. These people include and exclude artworks that are to be showcased at a museum or an exhibition. There are a complicated set of factors that influence their selections like quality, relevancy with the aim of the exhibition, etc. Through this act of curation, the audience of the exhibition is also filtered from what is limited to be included. Hence, these people—aside from art critics—help to shape the taste of the exhibition’s audience. In contrast, mass art products like films, anime, and manga, work differently since their success is measured by the number of consumers and profit.

However, this hierarchy in the arts has gradually changed with the introduction of the Internet. The technology eases people’s access to media and provides a greater degree of freedom to express their tastes, whether through creation, distribution, or, as we are discussing, appreciation (Janssen & Verboord, 2015). In the appreciation culture on the Internet, it’s easier to trust others who have the same taste compared to the traditional gatekeepers. This a phenomenon that has been referred to as post-truth, where information or messages are considered trustworthy based on emotion, not rationality, even when the information is fake or wrong.

Curiously, although the influence of traditional art gatekeepers weakens in this environment, the hierarchical gatekeeping culture itself merely shifted to new actors. In the Indonesian context, for example, it’s not rare to see people who are thought to be more experienced and/or more knowledgeable in a certain fandom or community being regarded as a “sepuh” [literally meaning “elder”, the term indicates seniority but is more loaded with reverence—editor], regardless of their other qualifications or whether it is actually in their capacity to make any statement in said field. This relation can appear like a traditional master-student relationship, where the “student” would follow whatever the “master” said.

The greater freedom to appreciate has also made some people feel that they need to act as gatekeepers in their pop culture fandom. The friend I mentioned before told me that this is to make sure that new fans won’t bring any “unnecessary influence” that can “disturb” the culture that has already been accepted within the fandom. This mindset has lead to community members often acting like immigration officers towards newcomers.

One of the ways that attitude takes form is in the act of “hazing” newcomers to instill the community’s culture and “rules”. An example of this can be seen in the “Attack on Titans is created by Garena” meme that went viral in Indonesia, when misinformed younger fans were relentlessly mocked for mistakenly thinking that Attack on Titan was created by a smartphone game company.

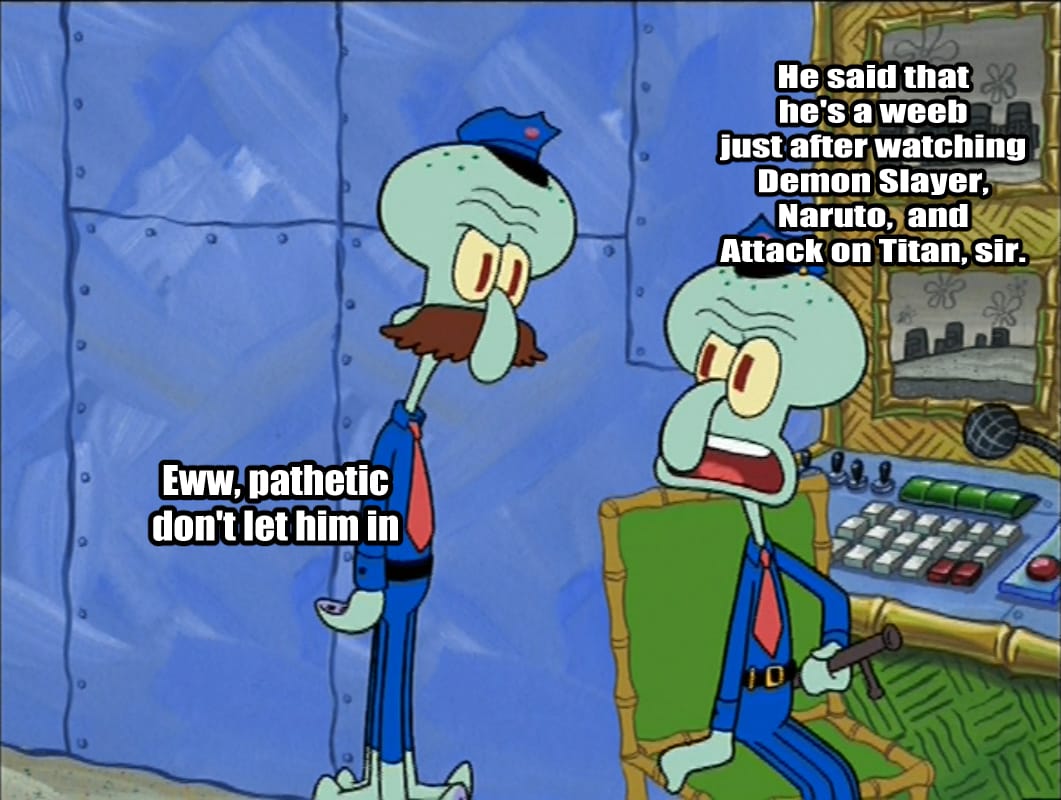

Another way this attitude has taken form is in a kind of elitism in the anime and manga community, where senior members of the community feel they can reject new members who do not follow the “rules” as they understand them. I view this to be a tool to maintain group exclusivity, barring people who are deemed not “qualified” from joining their fandom.

This has manifested, for example, in the often recurring opposition to those so-called “social justice warriors”. As the narrative goes, it is necessary to kick out those who disrupt “our” culture, enjoyment, and escapism with “feminist issues”. While it is true that there are times these issues have been brought up through confrontational means that leads to more noise than in building a clear understanding of the issues, it doesn’t mean the issues themselves, such as about the objectification of women, for instance, do not have merit to be discussed in anime and manga space too.

Another “casualty” to this situation are people who identify themselves as otaku (or as weebs, or whatever) but are treated as fake ones by others because they only watch shows that are deemed to be “mainstream” anime (often shonen titles or action anime that are easy to digest). They are often said to need to watch more, less popular anime or manga first before they can call themselves otaku.

Next Page: Lewin’s model of gatekeeping.