This is a translation of a piece originally written in Indonesian in early 2015 near the date of Comic Frontier 5, a local Comiket-like event, in the hope of encouraging further studies on the participation in Comic Frontier. In addition, in the mid-2010s, there have been talks among male anime fans about how “fujoshi suddenly appeared and ruin anime.” Thus, another aim of this piece at that time was to say to those group of fans that yaoi fans have been active in developing their creative expression for decades. However, admittedly the approach taken by this piece is not without its own bias, which oversimplifies interactions between different groups and glosses over the male creators’ antagonism towards female creators at Comiket. Do NOT take this piece as authoritative or expert source, and instead please check and learn from the references cited (which are pretty easy to access).

The Comic Market, also known as Comiket for short, is one of the events in which dōjinshi or independently published amateur creative works (particularly in the form of comics) are traded directly. The Comiket, which is held twice per year, is the largest of such events in Japan, with the number of visitors could reach over 500 thousand people (Comic Market Preparations Committee, 2008). This article aims to highlight a number of interesting things about the participation of women in the relam of dōjinshi culture in Japan, particularly in Comiket. These highlights reveal that women have been an important part of this culture and lend significant influence on its development.

The Majority of Participants in Dōjinshi Events are Women

In various dōjinshi market events, including Comiket, the majority of their participants are actually women. The data provided by the Comic Market Preparations Committee shows that since Comiket was first held in 1975 up to until at least 2008, participation had been dominated by women, especially among dōjinshi artist circles selling their products in the event (Comic Market Preparations Committee, 2008; Wilson dan Toku, 2003). Though according to direct observations conducted by Matthew Thorn (2004: 171, 182), Comiket actually has relatively larger proportion of male participants compared to other dōjinshi market events in the country, and throughout the 1990s the gender proportion had become somewhat more balanced. Outside of the core activity of dōjinshi trade, attendants who come to cosplay are also mostly women (Comic Market Preparations Committee, 2008).

The Popularity of Yaoi is one of the Triggering Factors of Lolicon Boom

One of the most popular genres in dōjinshi, especially among women is yaoi, a genre that usually depicts intimate relationships between male characters from popular anime series (Thorn, 2004: 171-172). Yaoi emerged as early as in the 1970s (Kotani in Bolton et al., 2007: 223) and became very popular in the 1980s with the abundance of yaoi dōjinshi based on anime series such as Captain Tsubasa or Saint Seiya (Thorn, 2004: 171-172).

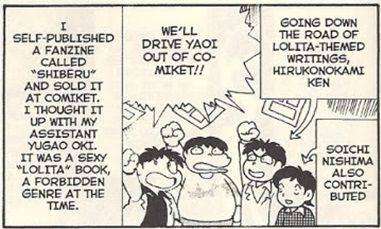

During their early days, the prevalence of female participants and their subjects of interests in dōjinshi markets had made male dōjinshi artists felt alienated. In response to the freedom that yaoi dōjinshi demonstrated in exploring eroticism in the relationships between male characters from popular anime series, certain male artists such as Hideo Azuma and his colleagues were motivated to made their own dōjinshi that explores eroticism of female characters drawn in cute, cartoonish style (Galbraith, 2013: 288). The work of Azuma and company, titled Cybele (Shibeeru), was then regarded as a pioneer that initiated the popularity of lolicon themes in the 1980s, also known as the lolicon boom (while yaoi also had its own boom in that period). Because of that, Azuma is renowned as the father of lolicon.

In short, the emergence of yaoi dōjinshi helps to push the emergence of lolicon-themed dōjinshi. Despite their different contents and appealing to different groups of fans, their histories are actually closely intertwined.

The Dynamics of Interaction between Male and Female Fans

As observed by Thorn (2004: 182-184) in the 1995 Comiket and one other dōjinshi market in 1993, female and male participants tend to socialize separately. As minority participants, males that enjoy erotic dōjinshi depicting cute girl characters were viewed with suspicion by female participants that enjoy yaoi. But as the proportion of male participants in Comiket increased, interaction between male and female participants also experienced some sort of shifts. Observing the Comiket again in 1998, Thorn took notice that other than all-female and all-male groups that attended the Comiket, there are also groups consisted of both women and men. Occasionally, some women came over the men’s group, and likewise, some men came over to the women’s group, changing the gender proportions in each group. He also observed couples among the attendants.

Thorn (2004: 183-184) noted that when it comes to it, for both female and male participants, dōjinshi is a shared medium through which they could express their interests outside of the rigid social norms in daily life among Japanese society. Dōjinshi is a medium of interaction through which the otaku, both men and women, could share and form social connections in their own way.

Concluding Remarks

The history of the realm of dōjinshi culture as we know it had the influences of women’s participation taking part in shaping it. Therefore, women cannot be underestimated as a significant creative force in this culture. There are times when women and men that participated in Comiket viewed each other with contempt. However, through shared love for dōjinshi as a medium of expression and socialization, some shifts in attitude has opened the possibilities for women and men to be more accepting and amicable towards each other.

The above have been some interesting points to highlight from the participation of women in the development of Japanese dōjinshi culture. It ought to be interesting to make reflective comparisons between the developments occurring in Japan with the development of dōjinshi culture and communities in local contexts outside of Japan, such as in Indonesia.

References

- Comic Market Preparations Committee. “What is the Comic Market?” February 2008 presentation. Retrieved from http://www.comiket.co.jp/info-a/WhatIsEng080225.pdf.

- Galbraith, Patrick W. “Osamu Moet Moso: Imagining Lines of Eroticism in Akihabara.” Mechademia, Volume 8, 2013. pp. 279-297.

- Kotani, Mari. “Introduction” for the chapter on “Otaku Sexuality.” Bolton, Christopher, Istvan Csicsery-Ronay Jr., and Takayuki Tatsumi (editors). Robot Ghosts and Wired Dreams: Japanese Science Fiction from Origins to Anime. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007. pp. 222-224.

- Thorn, Matthew. “Girls and Women Getting Out of Hand: The Pleasure and Politics of Japan’s Amateur Comics Community.” Kelly, William W. (editor). Fanning the Flames: Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan. Minneapolis: State University of New York Press, 2004. Halaman 169-187. Available in http://matt-thorn.com/shoujo_manga/outofhand/.

- Wilson, Brent, dan Masami Toku. “Boys’ Love,” Yaoi, and Art Education: Issues of Power and Pedagogy.” Retrieved from http://www.csuchico.edu/~mtoku/vc/Articles/toku/Wil_Toku_BoysLove.html.

By Halimun Muhammad | The writer is an alumnus of the Faculty of Social and Political Science of the University of Indonesia with interest in exploring academic studies on anime culture and its fandom

[…] many male attendees, including aspiring mangaka Hideo Azuma. Azuma and his colleagues decided to “drive out” the gay male manga by forming a doujin, working under pseudonym, and releasing their own far more sexually explicit […]