Within anime and manga fandom, there is a category of fans known as fujoshi. Fujoshi refers to female fans that enjoy stories depicting intimate relationships between male characters, a genre known as boys’ love (BL) or yaoi. As a part of anime and manga fandom, fujoshi actually still experience some misunderstandings from other fans with different interests. Here are five myths on fujoshi that can be disproven with observable evidences from Japanese fujoshi as well as Indonesian fujoshi.

Myth 1: All women that like anime and manga are fujoshi.

There are women who are not interested in BL and yaoi and have a more general interest on anime and manga (Galbraith, 2011: 220). In his research on Japanese otaku, Patrick Galbraith (2012), encountered female informants, among whom there is one who like collecting various kinds on character figurines (62-66), or liking yuri (stories about romantic relationship between female characters) instead of BL/yaoi (136-140). Even among fujoshi themselves, there are some that moved on from their interest on BL and yaoi because of responsibilities at work or home (Galbraith, 2011: 227-228). However, as communications technology and social media developed rapidly in recent times, accessing BL/yaoi contents, as well as fellow fujoshi becomes much easier and allow fujoshi to maintain their interest on BL/yaoi despite their growing social responsibilities (ibid., 229).

For an Indonesian perspective, I had a fujoshi from one of the most renowned university in Indonesia as an informant. She informs that in the anime and manga community in her campus, there are a number of female anime and manga fans who are not obsessed with BL/yaoi, though their numbers are small. She also recounts that there are some fujoshi who moved on from BL/yaoi, either because of pressure from her boyfriend or because of joining a religious study group.

Myth 2: Fujoshi don’t have any interests other than BL/yaoi.

There are fujoshi that other than liking BL/yaoi, also possess a more general interest in anime and manga. One of Galbraith’s informant in his study Galbraith (2012: 110-116) is a young woman who describes herself as “70% fujoshi, 30% otaku.” Other than collecting BL/yaoi-themed dōjinshi (independently published amateur comics), she also collected CDs of popular singer and seiyū such as Nana Mizuki, possess some figurines of male and female characters, as well as having played Tokimeki Memorial when she was still in elementary school.

My informant fujoshi also has varied interests. Among them are watching Super Sentai, and reading various books ranging from detective novels, to journey-themed light novels such as Kino’s Journey or Spice & Wolf, to books about traveling. Within her community in campus, there are also fujoshi who is fond of female idol groups such as Perfume and Momoiro Clover Z, including the idol-themed anime Love Live!; as well as doing covers of their songs.

Myth 3: Fujoshi is a new phenomenon.

Fans of BL dan yaoi in Japan has existed for about 40 years. Pioneers of BL-themed works appeared in the 1970s, with the serialization of such works as Thomas no Shinzō (The Heart of Thomas) by Moto Hagio in the magazine Shōjo Comic in 1974, and Kaze to Ki no Uta (The Poem of Wind and Trees) by Keiko Takemiya in the same magazine in 1976. Later, female fans were inspired to portray male characters from popular anime in intimate relationships through the medium of dōjinshi. Female fans have indeed dominated participation in the Comiket since its inaugural event in 1975 (see also the article “Women and Yaoi in Japanese Dōjinshi Culture”). In the 1980s, yaoi-themed dōjinshi based on anime series such as Captain Tsubasa and Saint Seiya were abundant in Comiket and made yaoi to be very popular. This rapid growh of yaoi dōjinshi in Comiket because of the popularity of those anime series was later remembered as a period of yaoi boom (Lam, 2010: 237).

Myth 4: Fujoshi only likes pretty boys (bishōnen).

There are a plenty of manga and anime with dominantly pretty faced boy (bishōnen) characters such as Prince of Tennis, Kuroko no Basket, or Free! that fujoshi are interested in. It gives the impression that fujoshi only like bishōnen characters. The truth is that fujoshi’s favorite character types are quite varied. There are those who like buff, muscular characters, or oyaji/ossan (older man) characters (Galbraith, 2011: 222). My informant fujoshi confessed that she likes to pair Jigen and Lupin from Lupin III. Outside of anime and manga, she also likes to pair Agatha Christie’s detective character, Hercule Poirot with his companion Hastings, or pairing the dwarf king Thorin with Bilbo from The Hobbit. One of her fellow fujoshi in the campus community likes the type of characters described as “humble ossan” and among her favorite characters include Shigeyuki Murakoshi from Giant Killing and Juichi Fukutomi from Yowamushi Pedal.

In a closer look on Yowamushi Pedal, which is currently one of the more popular titles among fujoshi, the character designs for the most part are not the typical bishōnen kind. Also, looking back at the history of yaoi boom in the 80s, its main trigger Captain Tsubasa has character designs that are more of a simple, cartoonish style. On the other hand, Slam Dunk which has also been a major source of inspiration for yaoi dōjinshi in the 1990s (Thorn, 2004: 172), has character designs that looked more “realistic” and “macho.”

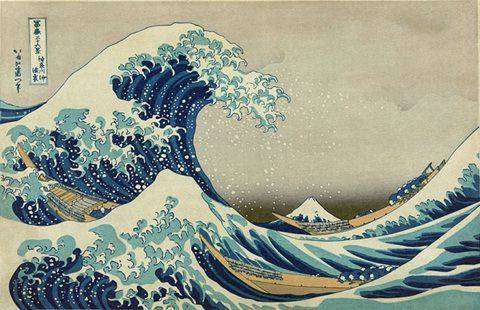

Fujoshi’s sources of inspiration are not only limited to characters from fictional works or actual humans, but also things they encountered in their daily lives. Fujoshi can turn a car and the road into a yaoi couple, or even pairing the wave and the boatman from Hokusai’s The Great Wave Off Kanagawa woodblock print (Galbraith, 2011: 226-227).

Myth 5: All yaoi are explicit and has no plot.

Depictions of intimate relationships between male characters in BL and yaoi works don’t always involve explicit depictions of sexual intercourse. Some only went as far as depicting the characters holding hands. (Galbraith, 2011: 212), some depict awkward moments of two boys being together, or simply leaving hits of intercourse without actually depicting it (Thorn, 2004: 172). Manga scholar Matthew Thorn (ibid) also mentioned that some of the newer yaoi works has genuine stories with plots that can stretch in many volumes.

In one of Jakarta’s own dōjinshi market event, the 5th Comic Frontier, my informant showed me some of the BL-themed dōjinshi that she had purchased in the event. Said samples only depict the relationship and romantic tensions between the male characters in comedic manner. She also mentioned some BL artists who made works without explicit contents, such Kei Ichikawa, Asumiko Nakamura, Hideyoshico, and a handful more.

Concluding Remarks

There are actually plenty more interesting things that can be learned from fujoshi. Those things can only be learned through having an open mind in getting to know and socialize with the fujoshi and the things they are interested in, whether they related to BL/yaoi, as well as other stuffs not related to those.

Note

In their definitions, boys’ love and yaoi actually could refer to two different genres. But in practice, the two words are often used interchangeably lie sinonyms.

References

- Galbraith, Patrick W. Otaku Spaces. Seattle: Chin Music Press, 2012.

- Galbraith, Patrick W. “Fujoshi: Fantasy Play and Transgressive Intimacy among “Rotten Girls” in Contemporary Japan.” Signs, Vol. 37, No. 1, 2011. pp. 211-232.

- Lam, Fan-Yi. “Comic Market: How the World’s Biggest Amateur Comic Fair Shaped Japanese Dōjinshi” Mechademia, Volume 5. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010. pp. 232-248

- Thorn, Matthew. “Girls and Women Getting Out of Hand: The Pleasure and Politics of Japan’s Amateur Comics Community.” Kelly, William W. (editor). Fanning the Flames: Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan. Minneapolis: State University of New York Press, 2004. pp. 169-187. The article is available to be read in http://matt-thorn.com/shoujo_manga/outofhand/.

- Interview with informant in Desember 25, 2014, and discussion and observation in Comic Frontier 5, Januari 24, 2015.

By Halimun Muhammad | The writer is an alumnus of the Faculty of Social and Political Science of the University of Indonesia with interest in exploring academic studies on anime culture and its fandom | Images taken from Genshiken, Oreimo, Captain Tsubasa, Lupin III, Yowamushi Pedal, and Slow Starter