This essay contains spoilers.

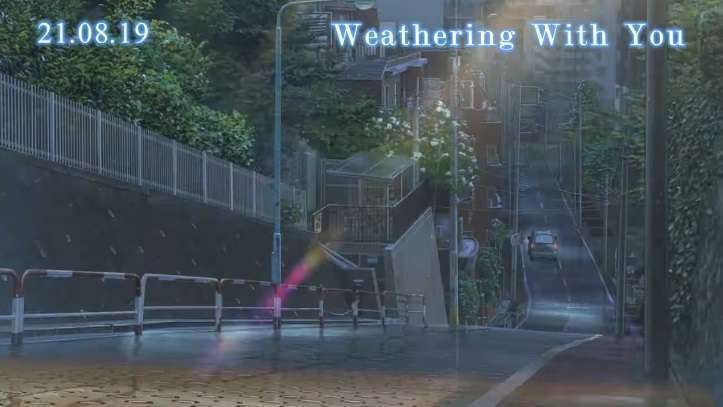

Watching Makoto Shinkai’s latest film Weathering with You (Tenki no Ko, 2019) induced a bit of nostalgia in me. Seeing the rain-soaked streets and corners of Tokyo brings me back to my trip to Osaka five years before. The light spring rain poured all day from the time I arrived at the airport, riding the train to the city, to getting dinner. Then, after four days straight of clear weather, the rain poured again in the morning I left for the airport to fly home. My visit to Japan was welcomed by sights of a city under the rain, and sent off by the same sight.

But more than just nostalgia, I did try to pay more attention to how the city of Tokyo is depicted in the film because of a discussion I listened to from Pause and Select and a paper I read about urban and rural spaces in the previous Makoto Shinkai film, your name. (Kimi no na wa., 2016). It’s as important as the film’s characters themselves how the film depicts the buildings and structures of Tokyo in so much detail, how it shows the vast cityscapes, and how it fills the city with beats of life from the trains and cars that passes to and fro, the people, old and young, who walk, run, or just sit and chat, and so on, both when it rains and when it is clear. The lovingly made image of the city is filled with movements that brings it to life (or in other words, “animate” it) with various people, things, places and all the relationships between them.

But how do the main characters, Hodaka, Hina, and Nagi, fit in in the life of the city? How much do they feel belong and have a place in it?

Overall, it can be said that the main characters of Weathering with You have tenuous relations with the city. Whether through losing their parents or having ran away from hometown, they live in the margins with little adult supervision, struggling to make their ends meet with their own work even though they are underage. While arguably their situation is not tenable in the long run, on the other hand the efforts of the authorities to solve their welfare issue in accordance to the law is counterproductive. Since even though they are based on good intentions, it involves removing the characters from relationships that matter, valuable, and mean a lot to them, that give them a sense of belonging. The authorities want to help, but without listening and paying attention to those they are helping.

Read more: Weathering with You review: “rebelling on instinct”

Following the schema of playwright Minoru Becchaku (Abel, 2011; Tanaka, 2013), if we consider the relationship between Hodaka, Hina and Nagi as the foreground of personal intimacy and Tokyo as the middle ground of collective life, there is also the the heavens, the weather, as the background, or the realm that operates beyond human understanding, pouring endless rain on the city for seemingly no discernible cause. This background is connected to the foreground relationship through Hina’s ability as the “sunshine girl” (hare onna), or rather, as a kind of medium between the heavens and the human world, who can wish for the rain to recede with certainty.

Hina, Hodaka, and Nagi offer that ability to people as a service to make a living (amusingly, what they do appears pretty similar to the well-known job of rain shamans in Indonesia, often employed by outdoor events to divert rain), and in the process, also allows them to make their own place among the city’s populace. But as the story progresses, it turns out Hina’s mediumship has to be paid with her sacrifice to the heavens, or the rain will continue perpetually. Why such a cost has to be paid is not necessarily made clear. But rather than oversight, it cements the background as the realm beyond the comprehension of human reasoning.

Seeing this scenario, I can understand why one of KAORI’s staff might identify sekai-kei characteristics in Weathering with You. The fate of the world is closely connected with the personal relations of the main characters, whose relations with society is tenuous, and within that personal relationship, there is the girl character who posseses special powers whose action becomes the key to save the world from crisis (Abel, 2011). Such apocalyptic motif is already pretty familiar among anime works, especially in the post-Evangelion era (1995), and one of Shinkai’s own older films, Voices of a Distant Star (Hoshi no Koe, 2002), is considered to be one of the most representative works of sekai-kei fiction (Tanaka, 2013).

But Weathering with You proceeds differently from what is considered typical in sekai-kei story, where only the action of the girl character is the key to the fate of the world, while the main male character is usually helpless and can only observe without facing the consequences of making the decision to act. (Tanaka, 2013). At the climax of the film, Hodaka made the action to retrieve Hina who had been taken by the heavens so that they and Nagi can gather together again, even though he knew the consequence of his action is that the extreme weather that has been lifted by Hina’s sacrifice will return. Regardless whether Hodaka’s decision is right or wrong, the key point is that he has not turn away from making a decision that has severe consequences. This is also a different approach from the way the film Summer Wars (2009) by Mamoru Hosoda has been considered to break away from the sekai-kei pattern, where not only the male characters, Kenji and Kazuma, act together with the girl character, Natsuki, but Natsuki’s entire family and also netizens from all over the world eventually come to their aid to save the world, uniting the foreground with the middle ground in facing a common crisis (Abel, 2011).

Furthermore, it also needs to be noted that the relationship between the foreground and middle ground in Weathering with You is not always as antagonistic as it might appear to be. Although life in Tokyo seems harsh and unaccommodating, Hodaka and others still desire living in the city, to be part of it and have their place in it. And as mentioned in the beginning, Tokyo is still portrayed very vividly by the film, so while the darker aspects of the city is acknowledged as parts of it, it still can’t help but to keep loving the city. Some adults around Hodaka such as Natsumi are also shown having difficulty in integrating to society themselves, making them figures that occupies a liminal space between the foreground and middle ground. The end of the film also indicates that the city life can adapt to the changes that happen in the greater world, which is implied would continue to change over time with or without human intervention, meaning neither the personal relationship nor the wel-being of the city needs to be sacrificed for the other.

What might such an ending mean? Critics have noted that the sekai-kei motif peaked at the turn from the 90s to 2000s (Tanaka, 2013), after the economic bubble burst and the Great Hanshin Earthquake and the Tokyo subway sarin gas attack struck in 1995. The generation who came of age during this period had been living through a relatively stable economic and socio-political conditions of a rapidly developing Japan, never experiencing the post-war devastation and the difficult period of reconstruction that follows. As discussed in a Pause and Select video, this generation had only known catastrophic disasters and mass unrests through works of fiction, such as through the film Akira (1988). But after the shocks of the 90s, the disasters that previously has only been seen in comics or on screen has become part of real life, or in the words of Kiyoshi Kasai, “every day is armageddon and armageddon is everyday” (Abel, 2011). It might be understandable if such feelings may still persist in some form after going through the Sendai earthquake and the Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster in 2011, and even in 2018 a string of earthquake, typhoon, flood and landslides struck various regions in Japan that the kanji for “disaster” (災) was chosen to be the kanji of the year.

It appears to me that Weathering with You is concerned about the possibility that disasters and crises that seem to keep coming endlessly can instill a sense of defeatism that limits action, and responds by telling a story where actions that can be taken, either by individuals or by the community, still have meaning to do. Hence, I also do not think that the direction of the conclusion argues against the role of human agency in causing or permitting the occurrence of certain crises or disasters like climate change or the Fukushima power plant disaster (before the disaster, there had been research warning about the possibility of massive tsunami that can overcome the plant’s sea wall, but neglected by Tokyo Electric Power Company that believed the probability of such tsunami occurring is too small to implement improvements to the plant’s sea defenses). But rather, the film simply wants to encourage the audience not to succumb to situations that feel like they are out of our capacity to control. Along with other stories in recent times that appear to test or challenge the sekai-kei motif in their own ways such as Summer Wars, Rebuild of Evangelion (2007-2020) and Darling in the Franxx (2018), I feel that their narratives tell that the “everyday apocalypse” is no reason to stop making actions, as long as there are still people valuable to us in our company.

That is why I feel that Weathering with You is still an interesting film in its own right. Watching it had brightened my day as, during and even after seeing it, my mind continues to be excited about the possibility of interesting questions that can be opened from it.

P.S .: The best girls in this film are the Pretty Cure cosplayer duo who use Hina and Hodaka’s rain-stopping service. That is all and thank you.

Further Readings

- Abel, Jonathan E. “Can Cool Japan save Post-Disaster Japan? On the Possibilities and Imposssibilities of a Cool Japanology.” International Journal of Japanese Sociology 20 (2011). 59-72.

- Nippon.com Staff. “A Disastrous Kanji of the Year? “Wazawai” Picked as Top Character for 2018.” Nippon.com (2018).

- Pause and Select. “Understanding Disaster, Part 2: Akira and the Postmodern Apocalypse.” YouTube (2016).

- Pause and Select. “Shadows of Fukushima (Your Name and Shin Gojira).” YouTube (2018).

- Krolicki, Kevin, Scott DiSavino, Taro Fuse. “Special Report: Japan engineers knew tsunami could overrun plant.” Reuters.com (2011).

- Tanaka Motoko. “Apocalyptic Imagination: Sekaikei Fiction in Contemporary Japan.” E-International Relations (2013).

- Thelen, Timo. “Disaster and Salvation in the Japanese Periphery. “The Rural” in Shinkai Makoto’s Kimi no na wa (Your Name).” ffk Journal 4 (2019). 215-230.

By Halimun Muhammad | The author is a graduate of the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences in Universitas Indonesia who has consumed anime and manga for more than ten years.