After waiting for three years, the Indonesian animated film Battle of Surabaya finally graced the theatres in the country on August 20, 2015. Since KAORI has reviewed the film, which can be read here, this essay will not retread doing a comprehensive assessment of the film. Instead, in this essay I would like to tread deeper into a particular aspect of this film that really impressed me when I watched it. I’m referring to how gender roles are played in the relation between the female main character of this film, Yumna (voiced by Maudy Ayunda), and the male main character, Musa (voiced by Ian Saybani).

What impressed me about that aspect is that in my view, it shows a quite progressive idea in the narrative of this film. It seems to resonate with the challenges posed to the conventions of action/adventure stories in Castle in the Sky (Tenkū no Shiro Laputa), the first film directed by Japanese filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki for Studio Ghibli. To make clear the comparison that I have drawn between the two films, this essay would first summarize the analysis of Thomas Lamarre on how the role of Castle in the Sky’s heroine undermines the conventions of action/adventure genre. Then this essay would explain how the play on gender roles between the main characters of Battle of Surabaya also undermines the genre conventions, although in different manners. Please note that this essay would have to spoil some important moments from both films.

Miyazaki’s Discontent with the Conventions of Action/Adventure Narrative

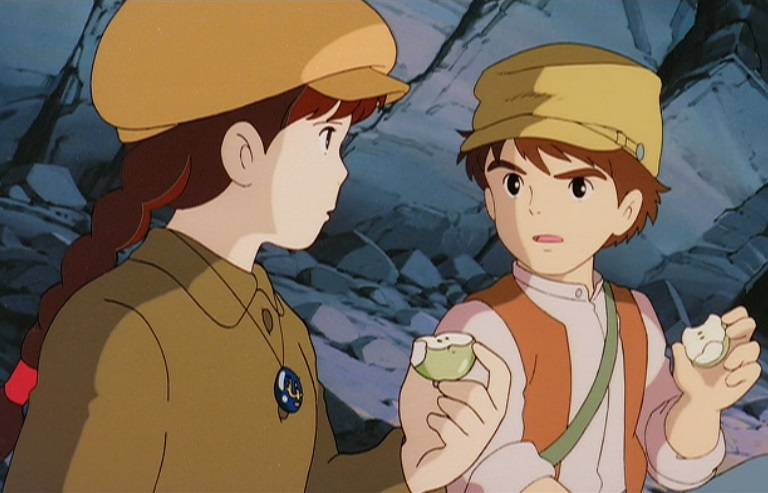

Castle in the Sky depicts a world that has been ravaged by weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) in the distant past. The flying fortresses that were the deadliest WMDs mostly has been destroyed, and regarded as mere legend by present generations. However, a group of people led by Colonel Muska intend to recover and took control of the remaining flying fortress, Laputa. The key to finding and controlling Laputa was held by a pastoral girl named Sheeta. The film follows the adventure of Sheeta in avoiding the pursuit of Muska and his men with the help of Pazu, a boy who found Sheeta after she has fallen to his mining city from an airship.

As described by producer Isao Takahata, Castle in the Sky is basically an action/adventure film. However, in a discussion with novelist Ryū Murakami, the director Miyazaki confessed that he had a feeling of discontent with action/adventure stories. Miyazaki’s concern was that these kinds of stories tend to depict a simple resolution where the boy hero defeated the villains, which solves all the problems in the story. Taking cues from Hubert Dreyfus’ essay on Heidegger’s thoughts and modern technology, Lamarre suggests that this genre convention is representative of a way of thinking in which humans take their conditions as problems that needs to be solved, to be controlled so that humans can gain benefit from solving it.

The stereotypical role of the main female character in action/adventure stories often supports that genre convention. The female lead is often put in a powerless condition, threatened by the villain and needs to be rescued by the male hero. After the villain has been defeated, the female lead becomes the lover of the male hero, as a ‘prize’ to him for saving her and the world from the threat of the villain. The female lead here is a mere object or a plot device.

Miyazaki does not want to simply reproduce such patterns. Through his own action/adventure film, Miyazaki instead undermines such genre conventions. Murakami noted that if Castle in the Sky is a mere conventional action/adventure story, then the hero would have defeated the villains and claim command of Laputa’s weapons to be used for good purposes. However, in the film, Sheeta dan Pazu instead activated Laputa’s self-destruct mechanism. As such, no one would be able to utilize Laputa, either for good or ill intentions.

According to Lamarre’s explanation, how Miyazaki played with the role of the film’s main female character is one of the important aspects that help to undermine the conventions of action/adventure genre. As the keeper of the magical stone that acts as the key to find and control Laputa, Sheeta became an object of pursuit by a number of factions. Through Sheeta’s plight, Miyazaki demonstrated to the viewers the stereotypical role of the female lead, a powerless plot device to be pursued and contested by others.

Having experienced those stereotypical ordeals, though, Sheeta ultimately played a key role in saving the world, for she is the one who took the initiative to activate Laputa’s self-destruct mechanism. Here, the female lead actively made the decision that saved the world from destruction, while the male lead supported her decision. Thus, Castle in the Sky is not just the adventure of the boy Pazu, but also the journey of the female lead Sheeta into becoming the world’s salvation. And that salvation came not through defeating the villains by becoming more powerful than them, but rather through the main characters freeing themselves from being bound to the main object upon which the film’s conflict revolves.

Lamarre also argued that Miyazaki tends to avoid romantic resolution between his male and female main characters, to avoid making his female character a ‘prize’ for his male character. Miyazaki rather stressed the depiction of relationship between his male and female main characters “as friends, partner, or allies.” At least in Castle in the Sky, this is accomplished by giving the same weight to Sheeta’s journey to salvation with Pazu’s adventure. Sheeta does not end up as a ‘prize’ for Pazu, as it is not Pazu alone who saved the world like typical male heroes. It was Sheeta who provide salvation with Pazu’s help.

In playing Sheeta’s role as such, Miyazaki avoided the glorification of male strength and violence typically depicted by conventional action/adventure stories. By making the main female character as the source of salvation rather than a prize to be won by the male hero, Miyazaki undermined the tendency of the genre to glorify the strength of male heroes and battles as solutions to problems. The role of the female character in this film offered a freedom from being bound into fighting towards a new paradigm to understand the human condition. Lamarre sums this up nicely in the title of the seventh chapter of his book, only a girl can save us now.

Continued in the next page