“… little if anything is known about the people called otaku in Japan. We talk about them but not to them; the discussion is almost entirely framed by mass media, which deals in stereotypes – easily recognizable characters and narratives.” (Galbraith, 2010)

The term of otaku has been closely associated with fans of anime, manga, and related media. But there are also controversies that complicate the discourse on otaku. Negative views from the society toward people who are deemed otaku and to the media they consumed has been around for decades. Though more positive images of otaku has emerged in recent times, such as through the story of Densha Otoko (Train Man, a tale of an otaku who helped a woman from harassment on a train, that gets himself a makeover so he can date her, which has been told through various media including a popular TV drama), but Kio Shimoku, the creator of Genshiken, a manga about a group of college otaku, felt that otaku in general are still seen as “being laughable and weird” (interview with Kai-Ming Cha and Ed Chavez, 2008).

As the quote at the beginning of this article mentioned, otaku discourse is dominated by narratives, images, and stereotypes circulated through media, including through anime and manga themselves. As anime and manga getting more widespread outside Japan, otaku and its controversies has also become known outside of Japan, especially among people who consume anime and manga. Some may accept and use the term to build a common identity as anime and manga fan. But on the other hand, there are people who refuse using otaku as an identity label for anime and manga fans citing negative connotation of the word in the country of its origin.

But debates among fans aside, otaku has also become a subject of interest for academic studies. Through various approaches including, but not limited to, ethnography, psychoanalysis, media studies, etc., research about otaku offers some alternatives to understand otaku more thoroughly.

What makes otaku interesting to be studied? Broadly speaking, there are at least two points of interest. First, otaku may be considered to show distinct patterns of interaction with the media they consume and of interacting with others through the media they consume. Studying otaku then, is taken as a part of understanding how developments in media technologies and contents affect social relations.

Second, interpretations of the otaku label, whether as a label from the society or as self-identification, can also be critically examined. Differing narratives that develop surrounding the label indicate how society reacts to new forms of media and new ways of interacting with media, and how media also (re)produce those narratives.

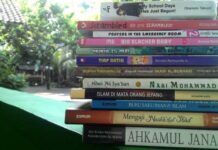

Here, I’d like to summarize a number of publications related to the studies of otaku. The selections could, hopefully, provide sufficient introductions to the various topics that can be explored in studying otaku, and encourage readers to learn more about them.

“Otakuology: A Dialogue” by Patrick W. Galbraith and Thomas Lamarre, in Mechademia 5: Fanthropologies, (University of Minnesota Press, 2010), pages 360-374.

A dialogue between two scholars, Patrick Galbraith and Thomas Lamarre. The dialogue covers the issues of the definition of otaku, what can studied about otaku and how to study it, as well as the implication and consequences of studying otaku. Coming from media studies, Lamarre sees otaku as a new form of social relation with and through media. Otaku do not consume media passively, but are active in reproducing meanings, derivative works, and even new social relations. Galbraith, through ethnographic approach, critically analyzes how otaku have been narrated through different temporal and geographic contexts, who narrated about them, and what are the consequences the various narratives about otaku that have developed.

“Otaku Culture as ‘Conversion Literature'” by Eiji Otsuka, in Debating Otaku in Contemporary Japan: Historical Perspectives and New Horizons (Bloomsbury, 2015), pages xiii-xxix.

The foreword from Eiji Otsuka for the book Debating Otaku in Contemporary Japan raises critical challenges for academics interested in studying otaku. Otsuka questions the political implication of otaku research by bringing in the historical and political context of the development of otaku culture, from wartime aesthetics, the conversion of postwar Left activists to media industry, the link between social stratification and otaku as an expression of social and cultural identity, up to the conservatism in Japanese politics in the present. Ignoring these critical contexts risks playing into the political interests of the Japanese government, which increasingly leans to conservatism in asserting its national identity trough propaganda projects such as “Cool Japan.”

“An Introduction to Otaku Movement” by Thomas Lamarre, in EnterText 4.1 (2004), pages 151-187.

In this article, Lamarre analyzes the contributions of Toshio Okada, Takashi Murakami, and Hiroki Azuma in understanding how the development of affective relations with visual media through anime results in an active otaku movement, producing and spreading their affections. However, unlike those writers, Lamarre does not see the otaku movement as a break from modernity, nor does he think the movement is something essentially Japanese. In his view, the otaku movement is formed from elements inherent in modern capitalist system, but produces patterns that do not resemble the constituent elements. For this reason, for Lamarre, the otaku movement is basically transnational in nature and cannot be fully controlled through corporate discipline. This gives an opportunity to imagine the possibility of an independent alternative space in the capitalist system.

“Otaku Sexuality” by Tamaki Saito, in Robot Ghosts and Wired Dreams: Japanese Science Fiction from Origins to Anime (University of Minnesota Press, 2009).

A practicing psychiathrist, Tamaki Saito considers the main characteristic of otaku in interacting with media is sexuality. Using psychoanalytic perspective, Saito explains the sexual desires of otaku and fujoshi (fans of works depicting homosexual relations between fictional male characters) to the fictions of bishojo and yaoi. Saito also writes the full-length book Beautiful Fighting Girl (translated by J. Keith Vincent & Dawn Lawson, University of Minnesota Press, 2011) and this book chapter can provide an outline of Saito’s theories from his own book.

imoku/Kodansha

The Common Sense that Makes the “Otaku”: Rules for Consuming Popular Culture in Contemporary Japan by Kam Thiam Huat (Thesis in National University of Singapore, 2008).

In this thesis, Kam sees otaku more as a labeling phenomenon and not as a group that can be categorized with certainty. From the interviews conducted for this thesis research, Kam found that otaku as a label is imposed on people who, in their activities of consuming popular culture, are considered to violate norms that are considered as common sense by the society. The norms that are violated are related to reality (otaku consumptions are thought to turn someone away from real life responsibilities such as work), communication (otaku consumptions are thought to make it difficult for someone to make social relationships with others), masculinity (otaku consumptions are thought inappropriate for “real” men), and majority (otaku consumptions are different from what the general population likes) values.

The Great Mirror of Fandom: Reflections of (and on) Otaku and Fujoshi in Anime and Manga by Clarissa Graffeo (Thesis in University of Central Florida, 2014)

In this thesis, Clarissa Graffeo looks at how otaku and fujoshi are depicted in anime and manga such as Genshiken, Welcome to The N. H. K., Lucky Star, and Oreimo. Graffeo examines how the positive and negative stereotypes in the depictions of otaku and fujoshi, and the depictions of their gender identity and sexuality in commercial media such as anime and manga, are influenced by both by social norms and market tastes (as can be seen in Lucky Star or Oreimo where the otaku characters are depicted as the types of characters favored by otaku themselves such as loli or imouto).

Otaku Spaces by Patrick Galbraith (Chin Music Press, 2012).

Though more of a pop publication, the book actually contains Galbraith’s raw research materials, interviews with people who are identified as otaku. The interview subjects are men and women, whose interests range from collect figures, collecting manga, playing visual novels, traveling to places shown in anime (also known as seichi junrei or “pilgrimage”), doing cosplay, making doujin illustrations, to decorating itasha, and many more. Some were still in college, while others have worked for a railway company, become models, or even had a family. Though they may show some stereotypical characteristics of otaku themselves, but differences in their interests, activities, and views pose a challenge to popular perceptions of otaku as a monolithic group.

Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals by Hiroki Azuma (translated by Jonathan E. Abel and Shion Kono), (University of Minnesota Press, 2009).

In this book Azuma explains that otaku reflects the general transition of society from the condition of modernity to post-modernity. The shift of otaku interests from anime which focuses on story to the consumption of moe character through small and self-produced narratives is thought to signify the loss of a great narrative or ideological struggle that is a historical feature of modern society.

By Halimun Muhammad | The writer is an alumnus of the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences of the University of Indonesia and enjoys anime and manga | This article was originally published in Indonesian at KAORI Nusantara on 25 June 2016 | Translated by Vina Nurziani A. A.